Weekly update 9

|

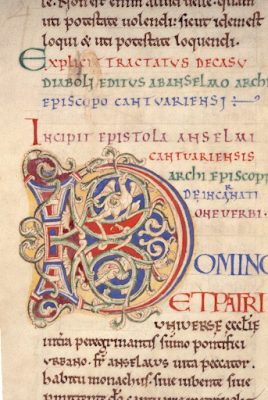

| The incipit of Anselm's letter On the Incarnation of the Word (Bodleian Library, MS 271, c. 1100-1140) |

In last week's entry I told the story of how Anselm reluctantly became archbishop of Canterbury. One of the threads in that story is Anselm's life as a monk, and I spent most of this week trying to figure out something illuminating to say about how his monastic profession shaped Anselm's life and thought. This turned out to be rather tricky. It's not as if there's anything in his treatises to which you can point and say, "Only a monk could have written that" (with the obvious exception of the bits where he says that he wrote a given work at the request of his brother monks). And yet the spirit of monasticism is somehow pervasive -- or so it seems to me. In the end I came to see some things I hadn't quite seen before.

In this week's excerpt I take a passage I've talked about before -- a somewhat neglected methodological passage in On the Incarnation of the Word -- and read it in the light of this new perspective.

*****

Monastic life shaped Anselm’s

thought in certain obvious ways: he developed arguments in conversations with

fellow monks; he wrote some works at their request or for their use; his

correspondence is filled with pastoral advice to monks and nuns about how to

live out their monastic profession. More striking, however, are the ways in

which his monastic embrace of obedience, authority, and common life arguably

shape even his treatises. For Anselm there is freedom in obedience and the

acceptance of authority: no longer a slave to his own desires, no longer burdened

with the need to make his own way in the world, a monk attains the liberty to

focus wholeheartedly on God. And this is true not only in the domain of action,

but also, perhaps preeminently, in the domain of thought. Acceptance of

theological authority is not a straitjacket; it does not inhibit creative

thought, but sets one free to think about “the deep things of God” with

confidence that one’s thinking will not go off the rails.

There is even a tantalizing

suggestion in Anselm’s letter On the Incarnation of the Word that obedience,

spiritual discipline, and meditation on Scripture—the core of the monastic life—can

enable someone to experience the truths of faith. “Experience” (experior)

is a word Anselm uses for first-hand acquaintance with something. Sensation is

a kind of experience: through my power of sight I experience something at first

hand and know for myself that it is present; I can speak of it with confidence

and clarity; I can knowledgeably invite others to experience it with me, because

I know where and what it is. If the obedient, disciplined, and meditative searcher

experiences the truths of faith in an analogous way, this would mean that through

the power of reason he would “see” those truths for himself; he could speak of

them with confidence and clarity from the store of his own experience; and he

could lead others—equally obedient, equally disciplined—along the meditative

path by which they too could see the truth for themselves, as if at first hand.

I hesitate to put too much weight on this one passage (for nowhere else in his

writings does Anselm speak of experiencing the truths of faith in this way),

but the suggestion is instructive, because it captures so much of what is

distinctive about Anselm’s theological writing. Though faithful to authority,

he almost never cites authority: why cite someone else’s testimony for a truth

that you have been able to see on your own? Other people may have given you

the maps, but you have explored the territory for yourself.

Comments

Post a Comment