Weekly update 5

|

| Edward Arthur Walton, "A shepherd and his flock at sunset" 1882 |

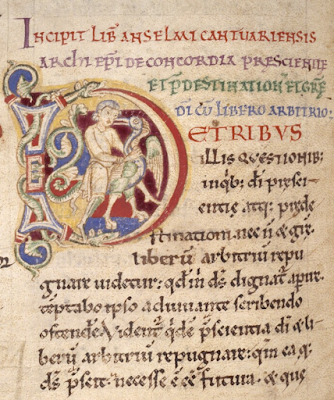

Still, it wasn't an entirely unproductive week, even on the book -- I do have an except, as usual. Plus I finished polishing all the additional translations for Anselm: The Complete Treatises and uploaded them here, where they will be available until the book is published in September 2022. On Wednesday I got some recording done for the Noonday Prayer podcast, which will return in Advent, and then (just to show that I have not entirely forgotten the name of this blog) I celebrated the Feast of Joseph Butler.

I've been watching the UK for some indication that I might be able to get to Scotland as planned in late July/early August. At this point it's looking as though the ten-day self-isolation will still be in place. I may just go anyway, dedicate those ten days to writing, and then get out and enjoy Edinburgh for a few days before my walking tour of the Isle of Skye.

This week's excerpt is a text box entitled "Why 'Father'?"

In the Monologion

Anselm does not use the word “God” (Deus) until the final chapter.

Up to that point he refers to “the supreme essence,” “the supreme nature,” and

“the supreme spirit.” The words for “essence” and “nature” are feminine, and

“spirit” is masculine (as “God” also is); “Word” is neuter. Why, then, the

exclusively masculine language of “Father” and “Son”? It is a mark of Anselm’s

independent-mindedness, and of the thoroughness of his project of faith seeking

understanding, that he sees the need to raise this question. There is no

distinction of sex in them, Anselm says (the point is so obvious it doesn’t

even require argument), so why not “Mother” and “Daughter” just as

appropriately as “Father and “Son”? You can’t say it’s because they are both

spirit (which is grammatically masculine), since they are also both truth and

wisdom (which are grammatically feminine). You can’t say it’s because in

sexually dimorphic animals the male is always stronger and better than the

female, because that’s not even true. Instead, the reason is that “the first

and principal cause of offspring is always in the father.” The mother is a

secondary cause. It would be inappropriate to apply a word designating a

secondary or inferior cause to “that parent who begets his offspring without

any other cause that either accompanies or precedes him.” So the divine parent

is a father: and since a son is always more like a father than a daughter is,

we should call the divine offspring, who is the perfect image of the Father, a

son.

Anselm thus has no argument for

“Father” and “Son” apart from his mistaken biology. Whether he would be

sympathetic to the contemporary impulse to avoid masculine language for God, or

instead seek some other argument to uphold the traditional language, is

something we cannot know. It is worth noting, however, that long before Julian

of Norwich famously addressed Jesus as “Mother” in her Revelations of Divine

Love, Anselm addressed not only Jesus but also Paul as “Mother” at great

length in his “Prayer to Saint Paul,” from which a brief excerpt follows:

Therefore, you are both mothers.

Yes, you are fathers, but you are nonetheless also mothers.

For you have brought it about—

you, Jesus, through

yourself; you, Paul, through him—

that we who are born

into death are reborn into life.

So you are fathers in the power of your effect,

mothers in the tenderness of your affection;

fathers in authority,

mothers in gentleness;

fathers in protecting

us,

mothers in pitying us.

Therefore you are both mothers.

Comments

Post a Comment