Weekly update 3

|

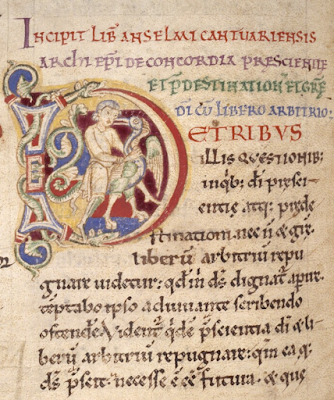

| Anselm hands over a work to Matilda of Tuscany |

I end my third week very slightly ahead of schedule, just beginning a new chapter, which deals with creation and assorted related issues (including the Trinity, as it turns out). This chapter is one of two that I don't basically have written in my head already--the other being the introductory chapter on Anselm's life, work, and contexts--so the next week or so may be rough going. But I'm encouraged by the progress I've made so far.

The excerpt I've appended is some basic but important stuff about the nature of God's causality. It originally included a digression about Humean vs non-Humean views of causality, including a hilarious (to philosophers) anecdote about two former colleagues of mine. I finally settled on the view that (a) "hilarious (to philosophers)" = "not remotely hilarious" and (b) only someone already corrupted by philosophy would entertain a Humean view of causation, so why make a big deal of it in a Very Short Introduction?

Anselm was fascinated by the

language of causation throughout his career, returning to different

fine-grained analyses of causal language again and again in his treatises. (He

also left some unfinished writings on the subject in what we call the Lambeth

Fragments.) Since he is open to using the word facere, to make or bring

about, in so many different ways, it is important here to note that he

understands God’s making or bringing about creatures as causality in the most

basic and direct sense. God acts knowingly and intentionally, and everything

other than God is an effect of that intentional act.

We have an intuitive feel for this

sort of bringing-about, because we experience causation all the time. I move my

fingers in a certain way over the keyboard and thereby cause a bit of Bach to

be played. I may not be able to say much about the mechanics—how the keys, the

hammers, and the strings all work together in producing the sound—but I have no

doubt that I have just brought about some music. I have experienced causation,

and I myself was the cause. This sort of causation, which philosophers call “efficient

causation,” is the kind of causality Anselm is ascribing to God with respect to

creation.

Yet although we can say that God’s

causality is of the same kind as the causality we experience in our own

actions and in the world around us, God’s exercise of that kind of causality is

quite different from ours. I need a piano to play, air for singing, paper on

which to write and a pen to discharge the ink, my natural powers of mind to

generate thoughts and arrange them. That is, I exercise my efficient-causal

powers on things that already exist, using powers that ultimately belong to my

nature: and my nature is not something that I have from myself.

God, by contrast, has (or rather is)

his nature from himself, a se, and he does not require pre-existing

things on which to exercise it. Moreover, God’s causality cannot be impeded, as

ours can: both my natural powers and the objects on which I exercise them can

fail me to various degrees. I want to sing, but my laryngitis is atrocious; I

want to jot down a note, but the paper is wet and, anyway, my hand is shaking.

God simply wills, and it is so.

Comments

Post a Comment